It’s a bright cold day in April, and you’d be forgiven for not knowing what time the clocks are striking. As social isolation digs further into one’s sense of meaning in the world, opportunities of escapism prove fairly useful, and I’ve founda good one.

As I only learned recently, in addition to being the most notable scientific journal in existence, Nature have a side hustle of publishing short fiction under a branch named Futures. And it’s class. While this particular future is one that they failed to predict, the column generally presents a prescient selection of science fiction that offers the behavioural sciences a preview of questions that they may have to ask eventually, and one featured story in particular sticks out to me right now.

‘What’s Expected of Us?’ by Ted Chiang offers a brief description of a reality where a device that (debatably) demonstrates a lack of free will is commercialized. Quickly, it spreads existential dread and meaninglessness amongst the population, a bit like a virus. It’s not really a complex point. When the sense, or locus, of control over one’s life evaporates, it become a lot more difficult to enjoy.

I can’t help but feel that ‘What’s expected of us?’ is a suitable question for behavioural policy units to be asking themselves at this point. After the term ‘herd immunity’ sparked a public relations disaster for the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team around a month ago, it appears as if a public that was previously unaware of behaviourally informed policy affecting their lives is now rather cynical about the attempts to do so.

Notwithstanding the fact that it seems the original behavioural covid response wasn’t overly evidence-based, it certainly felt that the backlash was amplified by the increased salience of there being a behavioural unit in existence in the first place.

Online outcry about the role of behavioural science in the UK government was typified by accusations that the discipline was no more than a variation of ‘digital marketing’ rather than science, as well as classic comparisons to Big Brother or Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. Obviously, these examples are sensationalist, but the sentiment is worth paying attention to. Behavioural Science arrives with the philosophy of helping people behave in positive ways that they would otherwise fall short of, but when this begins to interfere with one’s sense of autonomy, is this ambition a little misguided?

At the very least, on occasions such as this where behavioural resources are used for topics that go beyond issues like simple financial decisions, there is definitely a hint of ‘who watches the watchmen?’.

It’s not surprising from a psychological perspective that people are averse to other agents having an input into how their lives turn out, even when it’s ‘for the better’. On the back of decades of work spearheaded by Edward Deci & Richard Ryan (2017), Self-determination Theory identifies the central basic needs that underlie general mental wellbeing, one of which is autonomy. It’s not just that we want to feel in charge of our own behaviour, we kind of need to.

A Clockwork Orange envisions a system in which the powers at be can condition wrongdoers into making less bad decisions in future, and the free will of the individual is traded-off for a more moral, happy society. If you’ve never read the book or seen the film, there’s a chance that you may have at least seen an homage to it not once, but twice, in the excellent music videos of the Mercury-nominated slowthai.

The Northampton rapper’s Nothing Great About Britain last year became an iconic representation of the angst that exists between a government with a worrying amount of Oxbridge graduates and the sections of society that they don’t think about, so the visual metaphor used in Inglorious works perfectly. He doesn’t even leave it at visuals either, as heard in the track Dead Leaves:

Back here tomorrow

Clockwork Orange

I ain’t done a day of porridge

Don’t make me Chuck Norris

‘Cause I run my town but I’m nothin’ like Boris

The album and the book share a message: if those in power try to force you one way, push back by being a sort of ‘true self’. What is truly weird is that real life is somehow less optimistic than Burgess’ novel. In the book, while the behavioural intervention is extreme, it’s not effective long term, and the story concludes with a place for free will remaining in life.

In a piece I recently came across that hasn’t become outdated with time, Newman (1991) also uses A Clockwork Orange as a lens through which to view behavioural measures in government:

“If free will does indeed exist, then destructive interventions attempted by behaviorists will be ineffective and they will therefore be discredited, this will do more to destroy the influence of behaviorists than any philosophical treatise. If the behavioral interventions are successful, however, then we had better take them seriously.”

This is the thing. They do work. They. Work. Pretty. Well.

Of course, when Burgess wrote his novel, he wasn’t thinking about these sorts of policies with measurable social impacts. But when he wrote (on a Kantian wavelength) that “when a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man”, was he just being dramatic?

As a behavioural science student, I’m not sure what the answer to that is and that makes me somewhat uncomfortable. Behavioural interventions don’t restrict choice, but they do affect it when designed well. So, when you consider that alongside a climate where people are resistant to behavioural science units influencing them in the first place, the equilibrium position we are in seems a small bit fucked.

In Nothing Great About Britain, slowthai rebels against a government that doesn’t consider the interests of its people. When you note that SDT tells us that autonomy and a sense of control over one’s actions is key to wellbeing, perhaps behavioural science and its often-obfuscated motivations are in the firing line too.

However, if someone did argue against behavioural policies in an attempt to preserve the autonomy of citizens, therein lies an arguably trickier issue: free will is likely a cognitive illusion in the first place.

I began this post with reference to Chiang’s ‘What’s Expected of Us?’, and it’s a story not borne out of pure fantasy. Considering that models of behaviour propose that beliefs and actions are a result of genetic dispositions, personality traits and the environment you were thrown into, there is an enormous role for randomness, and no clear role for agency. Self-determination theory recognises an aversion to other agents having an input into how our lives turn out, but it could be even more difficult to deal with having no input ourselves.

Another, better, short story of Chiang’s is titled ‘Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom’, in reference to the existentialist Soren Kierkegaard (discussed in much better depth here). Kierkegaard proposed that the sense of discrete selfhood is illusory, so it is fitting that in this story Chiang examines a possible future where the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is proven and the effect this would have on one’s self-conception:

“People found themselves thinking about the enormous role that contingency played in their lives. Some people experienced identity crises, feeling that their sense of self was undermined by the countless parallel versions of themselves.”

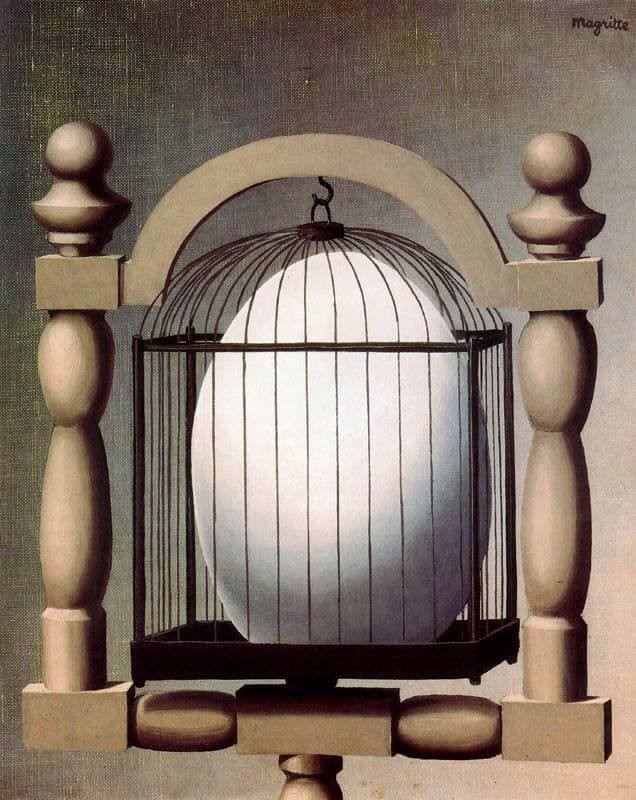

The fact that our lives could perceivably end up on countless paths, but that one has no agency over which path they end up on, has made for good fictional drama since Oedipus Rex. It’s seen in art also. In 1933, the surrealist Rene Magritte produced Elective Affinities, an illustration of how the will cannot be unbounded from external forces, using a pretty on-the-nose theoretical reference. It’s an entertaining idea to play with. However, it would probably not be as entertaining to be consciously aware of this at all times in your own life.

Applying this back to human decision-making, neuroscience too has found reason to push back against notions of discrete agency. In work such as Fried et al’s (2011), measuring neuronal activity allows researchers to predict how a participant will act in a basic choice paradigm before the participant themselves even consciously decides. There’s no doubt that the experience of freedom is strong, in fact it’s very convincing. But it’s likely a bit of clever decoration that’s bolted onto the true drivers of choice that we have no conscious control over.

One interpretation to this line of thinking would be that it’s thus impossible for behavioural science in government to undermine an individuals control over their own life, as it can’t exist, and even if they were hyper-conscious of factors influencing them they could never count them all. If that’s true then who cares if we’re influencing people that don’t want to be influenced? But that’s not really the point to care about, it’s the perception that’s more relevant.

I read a good line recently that said ‘it is agreeable sometimes to talk in primary colours even if you have to think in greys’. Given that most academic writing could be perceived as colourless in entirety, it’s not surprising that the best metaphor I’ve seen for this desire for the sense of illusory control comes from somewhere else. To borrow from 2019 hip-hop again, this time Billy Woods:

Life is just two quarters in the machine

But, either you got it or don’t that’s the thing

I was still hittin’ the buttons, “Game Over” on the screen

Dollar movie theater, dingy foyer, little kid, not a penny to my name

Fuckin’ with the joystick, pretendin’ I was really playin’

To revisit the core question of this post; in the decade to come, what are behavioural scientists for, and what’s expected of us? The last decade provides an evidence base that suggests that behavioural interventions can influence individual choice for a positive social impact, but what if it’s damaging to citizens to realise that their sense of agency/locus of control has been undermined? How do you calculate that trade-off?

One tactic is to avoid it altogether. This year, Lades & Delaney published the first easily comprehensible framework for ethical behavioural policy under the acronym FORGOOD. Having three O’s sort of spoils a good acronym, but that’s besides the point.

The first O stands for Openness and the R for Respect, defined as:

Openness – is the nudge open or hidden or even manipulative?

Respect – does the nudge respect people’s autonomy, dignity, freedom of choice and privacy?

These complement survey data that suggests members of the public are more likely to approve of nudges that operate under transparency and allude to the aversion people have to policy with obfuscated means and goals. Nothing surprising there.

Building on this theme though, there also exists a suggestion that it makes more sense to simply move a lot of behavioural interventions away from classical libertarian paternalism, and into the self-nudge realm. Instead of having to ask who watches the watchmen, you could simply enable a population of citizen choice architects to watch over themselves and their own biases. In that sense, policymakers wouldn’t be reducing autonomy, they could actually enhance it.

What’s sort of fascinating about that problem is, to almost certainly overdo the point, policymakers aren’t dealing with citizens’ autonomy at all. It’s the perception of autonomy that’s important. The locus of control. And it’s an absurdity that many behavioural practitioners fail to respect, so it should be intriguing to see how that evolves over the decade to come.

The public relations failure that was the BIT’s involvement in the UK’s coronavirus response signalled that there remains a lack of trust between the public and the discipline of behavioural science, and any further damages to this relationship run the risk of negating all the positive impacts that well-researched interventions can have in a modern society. In that sense it’s probably a good time to have such a wake-up call, while the falcon can still hear the falconer, and the buzz of Behavioural Science hasn’t yet been reduced to some sort of blunt hum.

But to truly earn the respect of the public, behavioural units could offer a little more respect too. People are probably quite averse to feeling that behavioural insights are impeding on their autonomy, even if it’s founded on an illusion. That’s not something that behavioural scientists seem to talk about all that much, and if they don’t start valuing it a tad more, it’s not clear what sort of beast slouches towards Whitehall to be born.