Like many others, I’m pretty prone to ending up spending evenings in weird YouTube rabbit holes. It’s actually impressive that their algorithm is accurate to the point where it can predict that you’ll click on things which you hadn’t even previously thought about.

This past week, my meanderings have been coloured by old clips from magicians Penn & Teller and their mildly successful TV show ‘Fool Us’. The premise is that every episode, new magicians perform onstage in the hope that the aforementioned pair of veterans fail to work out how their tricks work.

It’s fairly shit, but I like it.

Strangely, the moments that I find most endearing are not the rarer occasions where Penn & Teller are left stumped, but rather when they catch how the performer tried to fool them. In these instances where the skill involved is revealed, you’re quickly reminded of something that psychologists have known for decades, but magicians have known for hundreds of years: people rely heavily on their perceptions, we think that what we see is all there is, and this can be played with. If a magician uses your preconceptions to imply that something is happening, you’re likely to follow along.

Coincidentally, this point was recently reinforced via my other main source of procrastination, twitter.

It can be slightly discomforting to think that our understanding of our own experiences can be somewhat illusory, but I’m not sure that it should be ignored.

Bringing it back to magicians, one common technique that emphasises one’s false perceptions of their actions is that of forced card choice. With some professional level sleight of hand and sense of timing, a magician can tell you to pick a card at random, while being in total control of exactly which one you’re going to end up with.

What’s interesting in this interaction from a behavioural science perspective, as previously illustrated by Dr. Gustav Kohn, is that you’ll feel like you’ve had a genuinely free choice, even though you’ve been heavily influenced. It’s a simple enough point: just because you’re certain in your beliefs, it doesn’t mean that they’re correct.

While not shining an overly positive light on human cognition, this can at least be amusing.

The more alarming aspect of this, however, is that these misperceptions aren’t limited to shitty TV shows or tripping on birth control pills. Our strongest beliefs about the world and our place in it are probably subject to bias and illusions of understanding.

In a previous post, I tried to illustrate how crafting a narrative for your own life and drawing a sense of certainty from your experiences can make for an easier existence. But it has its drawbacks too. Being able to internally accommodate for your own inconsistencies helps build a cohesive sense of self from your own perspective, but it can pretty easy for others to observe instances where things don’t quite add up.

A few days ago, an article posted by the Bristol Post identified local men who publicly threatened the soon-to-be visiting Greta Thunberg online, one of which was still brandishing a ‘Be Kind’ filter on his profile picture in the wake of Caroline Flack’s suicide. It’s obviously an extreme, and pathetic, example to use, but it raises an important question of how capacities such as empathy actually work. Are most of us consistent people, or does it just suit us to believe that?

Regarding morality in the social and political domain, for a long time the implicit assumption has been that moral standings direct political leanings. However, current research suggests that this relationship operates in the opposite direction. Working off Social Identity Theory, this suggests that once we’ve planted ourselves amongst a cohesive group (such as an ideology), how we feel about policies and social issues is largely directed by influence of the group. Even if we feel like our reasoning is grounded in pure free will.

Without trying to overdo a basic point, having that artificial belief in the depth of one’s convictions makes life easier to live, but it does not mean that that sense of conviction is justified.

Empirical work from Fernbach et al. (2013) highlighted the point that political extremity is often supported by an illusion of understanding. Participants were recruited from the US, the most obvious focus of polarisation this decade, and were asked for their views on many popular issues. They were happy to declare themselves firmly for or against certain policies, but once they were asked to explain exactly how these policies would work, their attitudes moved back toward the middle. It’s not really any different from thinking you know how the zipper on your jeans works, until someone actually asks you to explain it.

Using the famous work of Phil Tetlock, you could say that we’re ‘naïve realists’ that are ‘prisoners of our preconceptions’. It’s good for our sense of certainty and being part of a consistent ideology fulfils several basic needs, after all it as an adaptive evolutionary feature, but it’s probably bad for democracy.

Another excellent experiment showing that the desire for self-cohesion can overpower the desire for accuracy was carried out by Strandberg and colleagues. Participants were asked to indicate their attitudes regarding various political statements, before later being re-shown their answers and prompted to confirm that what they had submitted was correct. What they didn’t know was that their own responses were manipulated, and some of the opinions that they were confirming were the exact opposite of what they had indicated.

Around half of manipulated attitudes were accepted by participants as being their correct view, and it didn’t matter if they were heavily politically involved individuals. What’s even more bizarre is that in a follow up session one week later, those that had accepted manipulated feedback had actually begun to shift their attitudes in that direction. We’re good at being consistent people, even if we’re not in control of what attitude we’re supposed to be sticking to.

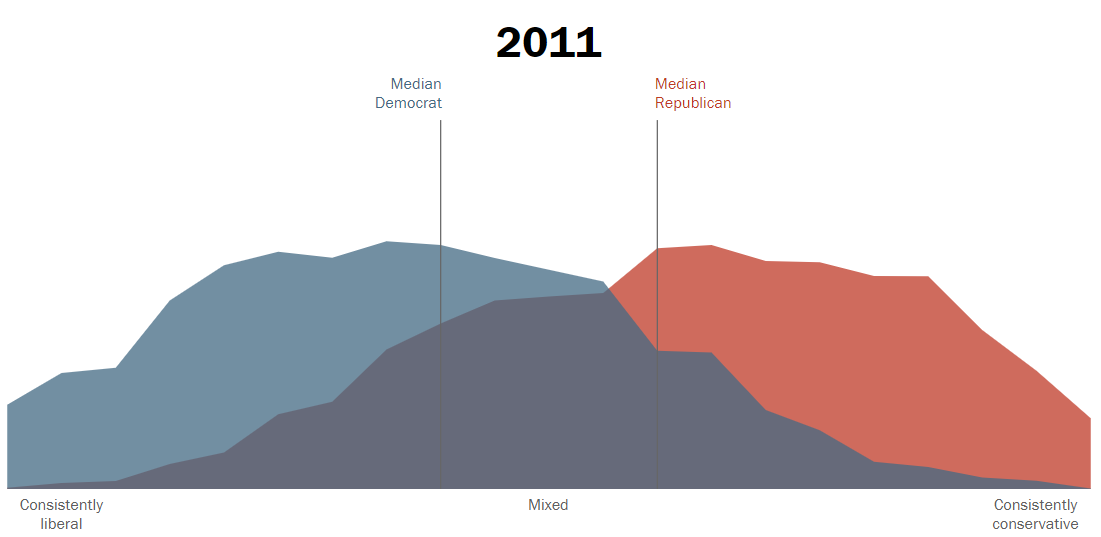

The immediate negative conclusion to draw here is that political attitudes are shallow, but perhaps an optimist would say at least they’re more flexible than we may have thought. The latter inference, however, is quite tough to justify when positioned alongside the current political landscape. Partisans disagree reliably and intensely and increasing polarisation between liberals and conservatives is supported by data. But how much of this divide in structured upon an illusion?

In the US, ordinary Democrats and Republicans consistently overestimate the difference in attitudes between them and the median voter of the opposite party, and this is exacerbated further as one incorporates their party as part of their identity. This furthers the sort of depressing notion that belonging to an ideology is more about fulfilling social needs of belonging and closure than actually forming accurate representations of society. To that end, it’s not much of a surprise that politicians with higher uses of collective words such as ‘us’ and ‘we’ tend to get elected more often.

I don’t want the point of this to be critical of the average voter and it would be hasty to use this evidence as reason to push back against pure democracy. But those participating in politics may be better served with an increased awareness of the factors that unconsciously affect them as well as their rivals.

Unfortunately, it’s truly unclear whether it is feasible to motivate people towards an environment where attitudes are revisable upon dissonant evidence, especially when it is natural to want to feel that your group is correct, and the other group is unquestionably wrong.

The Old Testament (I went to a Catholic school) tells the story of the Tower of Babel, where the whole of society came together to build towards heaven. Their punishment came from God confusing their language abilities, so that they could no longer understand each other, and the Tower couldn’t be finished. The resulting ‘confusion of tongues’ has since been famously portrayed in the work of Gustave Dore (below).

Partisan divides remind me a bit of that story. At some level we have collective goals to achieve a society where we can all be safe and happy, but it’s not clear how to talk to each other about it.

It might feel like an initial step would be addressing the fact that holding a political ideology is probably about more than knowing who you want to vote for, and the fact that most polarised opinions aren’t grounded in as much as knowledge as their holders believe.

These are misperceptions after all, but people hold them for a reason.

A partisan voter might not be as informed a citizen as they believe they are, but they probably feel very purposeful. They probably find a lot of meaning in their actions and reap benefits in their health and happiness as a result.

The guy from the tweet earlier didn’t take any Class A drugs, but the fact that he believed he did was enough for him to (I assume) have a pretty decent night. The ‘Be Kind’ guy that wants people to throw milkshakes at Greta Thunberg is clearly a hypocrite, but the fact that he can rationalise that helps him get up in the morning.

The fact that we can form structure from incoherence is a fairly remarkable achievement of perception and cognition, it just probably shouldn’t decide who ends up running our countries.

So how does Behavioural Science as a field attempt to fall into this? It’s a shame to say that it hasn’t really tried to yet. An excellent article from Sander van der Linden (2018) has previously addressed this point well, acknowledging that behavioural science and ‘nudging’ tends to purposefully avoid societies urgent but complex dilemmas, opting more towards low-hanging fruit and quick fixes.

It feels like behavioural scientists are at risk of patting themselves on the back a bit too quickly in how the area has developed. Polarisation of societies facilitates the exacerbation of our largest issues, from a lack of effective climate action to increasing wealth inequalities.

Yet even though we have a pretty developed set of fields describing why people make the choices they do and form the attitudes they carry; we don’t really seem to be doing much about it.

I think that’s something worth addressing.